Scripting

Typst embeds a powerful scripting language. You can automate your documents and create more sophisticated styles with code. Below is an overview over the scripting concepts.

Expressions

In Typst, markup and code are fused into one. All but the most common elements

are created with functions. To make this as convenient as possible, Typst

provides compact syntax to embed a code expression into markup: An expression is

introduced with a hash (#) and normal markup parsing resumes after the

expression is finished. If a character would continue the expression but should

be interpreted as text, the expression can forcibly be ended with a semicolon

(;). You can escape a literal # or ; with a backslash.

#emph[Hello] \

#emoji.face \

#"hello".len()

The example above shows a few of the available expressions, including

function calls, field accesses, and

method calls. More kinds of expressions are

discussed in the remainder of this chapter. A few kinds of expressions are not

compatible with the hash syntax (e.g. binary operator expressions). To embed

these into markup, you can use parentheses, as in #(1 + 2).

Blocks

To structure your code and embed markup into it, Typst provides two kinds of blocks:

-

Code block:

{ let x = 1; x + 2 }

When writing code, you'll probably want to split up your computation into multiple statements, create some intermediate variables and so on. Code blocks let you write multiple expressions where one is expected. The individual expressions in a code block should be separated by line breaks or semicolons. The output values of the individual expressions in a code block are joined to determine the block's value. Expressions without useful output, likeletbindings yieldnone, which can be joined with any value without effect. -

Content block:

[*Hey* there!]

With content blocks, you can handle markup/content as a programmatic value, store it in variables and pass it to functions. Content blocks are delimited by square brackets and can contain arbitrary markup. A content block results in a value of type content. An arbitrary number of content blocks can be passed as trailing arguments to functions. That is,list([A], [B])is equivalent tolist[A][B].

Content and code blocks can be nested arbitrarily. In the example below,

[hello ] is joined with the output of a + [ the ] + b yielding

[hello from the *world*].

#{

let a = [from]

let b = [*world*]

[hello ]

a + [ the ] + b

}

Bindings and Destructuring

As already demonstrated above, variables can be defined with let bindings.

The variable is assigned the value of the expression that follows the = sign.

A valid variable name may contain -, but cannot start with -.

The assignment of a value is optional, if no value is assigned, the variable

will be initialized as none. The let keyword can also be used to create

a custom named function. Variables can be

accessed for the rest of the containing block (or the rest of the file if there

is no containing block).

#let name = "Typst"

This is #name's documentation.

It explains #name.

#let my-add(x, y) = x + y

Sum is #my-add(2, 3).

Let bindings can also be used to destructure arrays and

dictionaries. In this case, the left-hand side of the

assignment should mirror an array or dictionary. The .. operator can be used

once in the pattern to collect the remainder of the array's or dictionary's

items.

#let (x, y) = (1, 2)

The coordinates are #x, #y.

#let (a, .., b) = (1, 2, 3, 4)

The first element is #a.

The last element is #b.

#let books = (

Shakespeare: "Hamlet",

Homer: "The Odyssey",

Austen: "Persuasion",

)

#let (Austen,) = books

Austen wrote #Austen.

#let (Homer: h) = books

Homer wrote #h.

#let (Homer, ..other) = books

#for (author, title) in other [

#author wrote #title.

]

You can use the underscore to discard elements in a destructuring pattern:

#let (_, y, _) = (1, 2, 3)

The y coordinate is #y.

Destructuring also works in argument lists of functions ...

#let left = (2, 4, 5)

#let right = (3, 2, 6)

#left.zip(right).map(

((a,b)) => a + b

)

... and on the left-hand side of normal assignments. This can be useful to swap variables among other things.

#{

let a = 1

let b = 2

(a, b) = (b, a)

[a = #a, b = #b]

}

Conditionals

With a conditional, you can display or compute different things depending on

whether some condition is fulfilled. Typst supports if, else if and

else expressions. When the condition evaluates to true, the conditional

yields the value resulting from the if's body, otherwise yields the value

resulting from the else's body.

#if 1 < 2 [

This is shown

] else [

This is not.

]

Each branch can have a code or content block as its body.

if condition {..}if condition [..]if condition [..] else {..}if condition [..] else if condition {..} else [..]

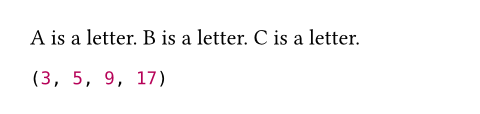

Loops

With loops, you can repeat content or compute something iteratively. Typst

supports two types of loops: for and while loops. The former iterate

over a specified collection whereas the latter iterate as long as a condition

stays fulfilled. Just like blocks, loops join the results from each iteration

into one value.

In the example below, the three sentences created by the for loop join together into a single content value and the length-1 arrays in the while loop join together into one larger array.

#for c in "ABC" [

#c is a letter.

]

#let n = 2

#while n < 10 {

n = (n * 2) - 1

(n,)

}

For loops can iterate over a variety of collections:

-

for value in array {..}

Iterates over the items in the array. The destructuring syntax described in Let binding can also be used here. -

for pair in dict {..}

Iterates over the key-value pairs of the dictionary. The pairs can also be destructured by usingfor (key, value) in dict {..}. It is more efficient thanfor pair in dict.pairs() {..}because it doesn't create a temporary array of all key-value pairs. -

for letter in "abc" {..}

Iterates over the characters of the string. Technically, it iterates over the grapheme clusters of the string. Most of the time, a grapheme cluster is just a single codepoint. However, a grapheme cluster could contain multiple codepoints, like a flag emoji. -

for byte in bytes("😀") {..}

Iterates over the bytes, which can be converted from a string or read from a file without encoding. Each byte value is an integer between0and255.

To control the execution of the loop, Typst provides the break and

continue statements. The former performs an early exit from the loop while

the latter skips ahead to the next iteration of the loop.

#for letter in "abc nope" {

if letter == " " {

break

}

letter

}

The body of a loop can be a code or content block:

for .. in collection {..}for .. in collection [..]while condition {..}while condition [..]

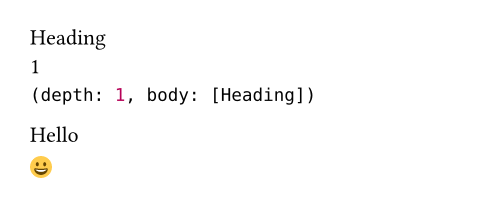

Fields

You can use dot notation to access fields on a value. For values of type

content, you can also use the fields function to list

the fields.

The value in question can be either:

- a dictionary that has the specified key,

- a symbol that has the specified modifier,

- a module containing the specified definition,

- content consisting of an element that has the specified field. The available fields match the arguments of the element function that were given when the element was constructed.

#let it = [= Heading]

#it.body \

#it.depth \

#it.fields()

#let dict = (greet: "Hello")

#dict.greet \

#emoji.face

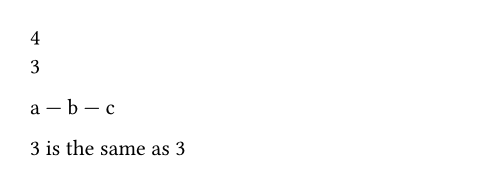

Methods

A method call is a convenient way to call a function that is scoped to a

value's type. For example, we can call the str.len function in

the following two equivalent ways:

#str.len("abc") is the same as

#"abc".len()

The structure of a method call is value.method(..args) and its equivalent

full function call is type(value).method(value, ..args). The documentation

of each type lists its scoped functions. You cannot currently define your own

methods.

#let values = (1, 2, 3, 4)

#values.pop() \

#values.len() \

#("a, b, c"

.split(", ")

.join[ --- ])

#"abc".len() is the same as

#str.len("abc")

There are a few special functions that modify the value they are called on (e.g.

array.push). These functions must be called in method form.

In some cases, when the method is only called for its side effect, its return

value should be ignored (and not participate in joining). The canonical way to

discard a value is with a let binding: let _ = array.remove(1).

Modules

You can split up your Typst projects into multiple files called modules. A module can refer to the content and definitions of another module in multiple ways:

-

Including:

include "bar.typ"

Evaluates the file at the pathbar.typand returns the resulting content. -

Import:

import "bar.typ"

Evaluates the file at the pathbar.typand inserts the resulting module into the current scope asbar(filename without extension). You can use theaskeyword to rename the imported module:import "bar.typ" as baz. You can import nested items using dot notation:import "bar.typ": baz.a. -

Import items:

import "bar.typ": a, b

Evaluates the file at the pathbar.typ, extracts the values of the variablesaandb(that need to be defined inbar.typ, e.g. throughletbindings) and defines them in the current file. Replacinga, bwith*loads all variables defined in a module. You can use theaskeyword to rename the individual items:import "bar.typ": a as one, b as two

Instead of a path, you can also use a module value, as shown in the following example:

#import emoji: face

#face.grin

Packages

To reuse building blocks across projects, you can also create and import Typst packages. A package import is specified as a triple of a namespace, a name, and a version.

#import "@preview/example:0.1.0": add

#add(2, 7)

The preview namespace contains packages shared by the community. You can find

all available community packages on Typst Universe.

If you are using Typst locally, you can also create your own system-local packages. For more details on this, see the package repository.

Operators

The following table lists all available unary and binary operators with effect,

arity (unary, binary) and precedence level (higher binds stronger). Some

operations, such as modulus, do not have a special syntax

and can be achieved using functions from the

calc module.

| Operator | Effect | Arity | Precedence |

|---|---|---|---|

- | Negation | Unary | 7 |

+ | No effect (exists for symmetry) | Unary | 7 |

* | Multiplication | Binary | 6 |

/ | Division | Binary | 6 |

+ | Addition | Binary | 5 |

- | Subtraction | Binary | 5 |

== | Check equality | Binary | 4 |

!= | Check inequality | Binary | 4 |

< | Check less-than | Binary | 4 |

<= | Check less-than or equal | Binary | 4 |

> | Check greater-than | Binary | 4 |

>= | Check greater-than or equal | Binary | 4 |

in | Check if in collection | Binary | 4 |

not in | Check if not in collection | Binary | 4 |

not | Logical "not" | Unary | 3 |

and | Short-circuiting logical "and" | Binary | 3 |

or | Short-circuiting logical "or" | Binary | 2 |

= | Assignment | Binary | 1 |

+= | Add-Assignment | Binary | 1 |

-= | Subtraction-Assignment | Binary | 1 |

*= | Multiplication-Assignment | Binary | 1 |

/= | Division-Assignment | Binary | 1 |