Context

Sometimes, we want to create content that reacts to its location in the document. This could be a localized phrase that depends on the configured text language or something as simple as a heading number which prints the right value based on how many headings came before it. However, Typst code isn't directly aware of its location in the document. Some code at the beginning of the source text could yield content that ends up at the back of the document.

To produce content that is reactive to its surroundings, we must thus specifically instruct Typst: We do this with the context keyword, which precedes an expression and ensures that it is computed with knowledge of its environment. In return, the context expression itself ends up opaque. We cannot directly access whatever results from it in our code, precisely because it is contextual: There is no one correct result, there may be multiple results in different places of the document. For this reason, everything that depends on the contextual data must happen inside of the context expression.

Aside from explicit context expressions, context is also established implicitly in some places that are also aware of their location in the document: Show rules provide context1 and numberings in the outline, for instance, also provide the proper context to resolve counters.

Style context

With set rules, we can adjust style properties for parts or the whole of our document. We cannot access these without a known context, as they may change throughout the course of the document. When context is available, we can retrieve them simply by accessing them as fields on the respective element function.

#set text(lang: "de")

#context text.lang

As explained above, a context expression is reactive to the different environments it is placed into. In the example below, we create a single context expression, store it in the value variable and use it multiple times. Each use properly reacts to the current surroundings.

#let value = context text.lang

#value

#set text(lang: "de")

#value

#set text(lang: "fr")

#value

Crucially, upon creation, value becomes opaque content that we cannot peek into. It can only be resolved when placed somewhere because only then the context is known. The body of a context expression may be evaluated zero, one, or multiple times, depending on how many different places it is put into.

Location context

Context can not only give us access to set rule values. It can also let us know where in the document we currently are, relative to other elements, and absolutely on the pages. We can use this information to create very flexible interactions between different document parts. This underpins features like heading numbering, the table of contents, or page headers dependant on section headings.

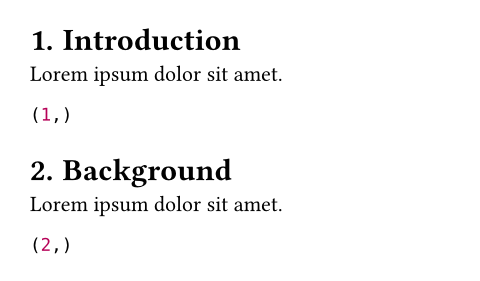

Some functions like counter.get implicitly access the current location. In the example below, we want to retrieve the value of the heading counter. Since it changes throughout the document, we need to first enter a context expression. Then, we use get to retrieve the counter's current value. This function accesses the current location from the context to resolve the counter value. Counters have multiple levels and get returns an array with the resolved numbers. Thus, we get the following result:

#set heading(numbering: "1.")

= Introduction

#lorem(5)

#context counter(heading).get()

= Background

#lorem(5)

#context counter(heading).get()

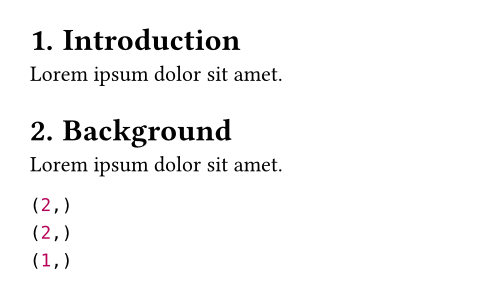

For more flexibility, we can also use the here function to directly extract the current location from the context. The example below demonstrates this:

- We first have

counter(heading).get(), which resolves to(2,)as before. - We then use the more powerful

counter.atwithhere, which in combination is equivalent toget, and thus get(2,). - Finally, we use

atwith a label to retrieve the value of the counter at a different location in the document, in our case that of the introduction heading. This yields(1,). Typst's context system gives us time travel abilities and lets us retrieve the values of any counters and states at any location in the document.

#set heading(numbering: "1.")

= Introduction <intro>

#lorem(5)

= Background <back>

#lorem(5)

#context [

#counter(heading).get() \

#counter(heading).at(here()) \

#counter(heading).at(<intro>)

]

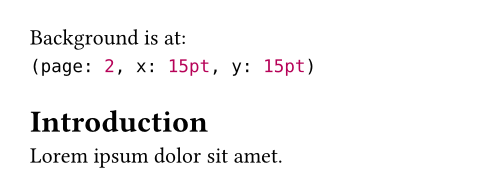

As mentioned before, we can also use context to get the physical position of elements on the pages. We do this with the locate function, which works similarly to counter.at: It takes a location or other selector that resolves to a unique element (could also be a label) and returns the position on the pages for that element.

Background is at: \

#context locate(<back>).position()

= Introduction <intro>

#lorem(5)

#pagebreak()

= Background <back>

#lorem(5)

There are other functions that make use of the location context, most prominently query. Take a look at the introspection category for more details on those.

Nested contexts

Context is also accessible from within function calls nested in context blocks. In the example below, foo itself becomes a contextual function, just like to-absolute is.

#let foo() = 1em.to-absolute()

#context {

foo() == text.size

}

Context blocks can be nested. Contextual code will then always access the innermost context. The example below demonstrates this: The first text.lang will access the outer context block's styles and as such, it will not see the effect of set text(lang: "fr"). The nested context block around the second text.lang, however, starts after the set rule and will thus show its effect.

#set text(lang: "de")

#context [

#set text(lang: "fr")

#text.lang \

#context text.lang

]

You might wonder why Typst ignores the French set rule when computing the first text.lang in the example above. The reason is that, in the general case, Typst cannot know all the styles that will apply as set rules can be applied to content after it has been constructed. Below, text.lang is already computed when the template function is applied. As such, it cannot possibly be aware of the language change to French in the template.

#let template(body) = {

set text(lang: "fr")

upper(body)

}

#set text(lang: "de")

#context [

#show: template

#text.lang \

#context text.lang

]

The second text.lang, however, does react to the language change because evaluation of its surrounding context block is deferred until the styles for it are known. This illustrates the importance of picking the right insertion point for a context to get access to precisely the right styles.

The same also holds true for the location context. Below, the first c.display() call will access the outer context block and will thus not see the effect of c.update(2) while the second c.display() accesses the inner context and will thus see it.

#let c = counter("mycounter")

#c.update(1)

#context [

#c.update(2)

#c.display() \

#context c.display()

]

Compiler iterations

To resolve contextual interactions, the Typst compiler processes your document multiple times. For instance, to resolve a locate call, Typst first provides a placeholder position, layouts your document and then recompiles with the known position from the finished layout. The same approach is taken to resolve counters, states, and queries. In certain cases, Typst may even need more than two iterations to resolve everything. While that's sometimes a necessity, it may also be a sign of misuse of contextual functions (e.g. of state). If Typst cannot resolve everything within five attempts, it will stop and output the warning "layout did not converge within 5 attempts."

A very careful reader might have noticed that not all of the functions presented above actually make use of the current location. While counter(heading).get() definitely depends on it, counter(heading).at(<intro>), for instance, does not. However, it still requires context. While its value is always the same within one compilation iteration, it may change over the course of multiple compiler iterations. If one could call it directly at the top level of a module, the whole module and its exports could change over the course of multiple compiler iterations, which would not be desirable.

Currently, all show rules provide styling context, but only show rules on locatable elements provide a location context.